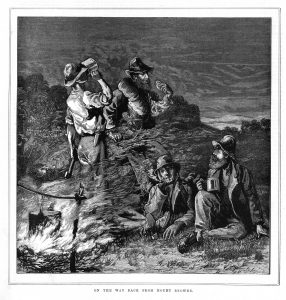

On the Way Back From the Mount Browne Diggings. Lithograph courtesy of the State Library of Victoria.

SAD DEATH AT MOUNT BROWNE.

A sad story (says the Bendigo independent) was contained in a letter received last week by a resident of Eaglehawk, who learnt the sad news of the death of his son at Mount Browne. The letter was from the mate of the young man in question, and stated that his friend had died from starvation. ‘The horrors of a prolonged drought are scarcely conceivable, still less the grief of a fond parent, who, a few short months ago, parted from his son, the latter in the full vigour of youth, buoyed up with the hope of bettering his fortune in a country that has proved the final resting place of many strong able bodied men.

Relevant Tib/Mt.Browne Links

The following article was published in The Sydney Morning Herald on Saturday the 22nd of September, 1951 and I feel it gives a pretty good idea of the landscape around Tibooburra.

The Central Australian Hotel, Tibooburra, circa 1925 with gum tree on the left. Photo courtesy of The State Library of New South .Wales

A Tree Grew In Tibooburra By GEORGE FARWELL

ALF REDPATH told me the story of the willow tree. He had lived in Tibooburra longer than anyone could remember; its second oldest inhabitant, getting close up 80. With his white, drooping moustache, pale eyes and frail, withered figure, he leaned against an old stable door in the yard behind the Family Hotel, drawing on a stunted pipe as though to extract from it the history of the tree. As it turned out, it was almost the history of Tibooburra. There had been a few changes in the four years since I had visited this little sheep township in the remote north-west corner of New South Wales, almost 300 miles back o’ Bourke. A five year drought had given way to a series of prolific seasons. Yet the township itself was little altered. Still the same small cluster of houses about a single wide and dusty street, enclosed by that strange rampart of tumbled granite boulders, like a Chinese wall in ruins. Only at a week-end does it really come to life, with cars from the scattered stations parked outside the two hotels. Now and again the Flying Doctor’s Dragon comes in to land across Dead Horse Gully with a patient for the little hospital, or a heavy mail truck passes through for cattle stations over the Queensland border.

WHAT had changed the whole appearance of the street was the missing tree. Therein, I had always felt was to be found Tibooburra’s unique character. A slender, leaning tree, it grew outside Tommy the Chinaman’s store, throwing the only patch of shade in summer’s heat. Tibooburra has been described as a township paved with gold, for you can fossick for specks in the main street after every shower of rain, but its barren soil has been less generous to growing things. It was a hardy little tree, native only to Western Queensland. Taking half a century to struggle up to 20 feet, it had hung on where others failed.

“I remember him being planted,(the tree was always a him to me)” said Alf Redpath. “That was back in ’95. Couple of young coves brought him in from Yalpunga, by the Queensland border gate. Used to be a post office and horse change for the mails one time. Now there’s only a tank for travelling stock. He was a mere shoot in a post-hole, outside the general store. They found him because his suckers were twined around a pepper tree and that had perished for want of rain. They’d never seen two trees twining around each other before so they planted the willow in a Cossack boot—y’know, the old style of lace up stockman’s boot—and they fetched him in on the Yalpunga mail coach to Tibooburra.”

“Well, Tommy the Chinaman was shook on the idea of this willow sapling outside of his door. He used to water it. By ghost, water was needed in those years! Remember that grand-father of all droughts starting in 1901? He was a good poor beggar, Tommy, and he kept a few squatters going in the lean times. You’d get anything you asked for in his store and, when he passed in the marble, he was worth a few thousand.”

“TOMMY the Chinaman looked after that tree. There was a peppercorn further up the street, and a gum sapling, but no one watered them ever. They struggled up to about nine foot high, then chucked it in. The willow had a lot to contend with, too; dry spells, the hot nor’-westerlies of summer, dust storms year after year. There’s never been too much water to spare. You’ll notice we’re not even using the camels this year to draw the watercart. The tank outside the town’s gone dry, and we’ve a truck carting it from Whittabrinna station. When he was a sapling, the goats gave him a bit of a time. So did the camels, when the old Ghans brought their strings up from Wilcannia and Broken Hill. When motor trucks started carrying the wool instead—and that weren’t until 1926—they’d often park under this tree for a bit of shade.”

“Now there’s a few flowering gums been planted, down by the other pub—but none’s got the character this native willow had. Nor the shade. That’s what Tommy always thought. Remember Frank Foster? Used to be stock inspector here, and painted pictures. He did a sketch of old Tommy one time, standing outside his store. Tommy looked at it, and he said “That not Tommy. Where’s that willow tree?” And he had to do the sketch again.”

I RECALLED Frank Foster well, for it was his collection of fossils, petrified wood and prehistoric bones which had given me the key to this country of low rainfall and recurrent drought. Men have learnt to cherish the good seasons here, just as they value individual trees where timber is scattered and small.

“I used to warn Tommy,” Alf Redpath said, “those roots were none too good. One day, I said, that willow’ll fall right on top of your store. But he’d passed away by the time it happened, and his roof was never hit at all. The tree blew down in a dust storm, and only the stump was left. People had grown so used to him that young Mr. Blore come in from Mokeley one day and parked his car in the usual spot, never noting the tree had gone. He’d hung it right on the stump, so we had to get it lifted off … “

In the lifetime of that tree the gold rushes out by Milparinka had swelled and ebbed, prospectors had set up their dry blowers beneath Tibooburra’s granite outcrops, the long camel trains had passed silently north with stores, back again with bales of wool, graziers had taken up huge properties, prospered and gone broke, shearers had knocked down their cheques in extravagant sprees, and cattle drovers coming down from Queensland hitched their horses to its trunk. Perhaps Alf, too, had grown aware that age could no longer indulge the roving spirit attached to sheep droving and station work. At all events, when the tree fell two years ago, he made it the occasion for an extended sojourn in the hotel across the road.

But this is a story with a sequel. “There’s a bit of a sapling coming up,” he told me. “It’s a wild willow outside the old Court House—some 20 yards away. Wind must have carried that seed along. Must have lodged in a crack there, got smothered by dust and grew. Thats the old tree’s offspring. The old fellow’s passed his life on, and he’s growing again.” There it is—the essence of the Far West, sheep dying in their thousands, then new herbage springing up and dry lakes full. In Tibooburra a wild willow still grows.

Relevant A tree grew in Tibooburra Links